My life officially began in Leningrad, Russia, and you have guessed correctly that there was no Black History Month there. I spent four years of my life in Russia before my parents moved us back to Nigeria. I do not remember much of my life in Russia, but my parents have told me the story several times of how I was once called a monkey because I was black. I do not recall this, so it does not affect me in anyway. I still dream of going back to visit Russia someday.

After Russia, I spent some time in Nigeria before moving to America where I have now lived for most of my life. And America, is where this great story matters. In Nigeria, I was an Igbo girl (from the Eastern part of Nigeria) who lived in Jos, Plateau State (the Northern part of Nigeria). If you wanted to get specific, then I was Igbo, from Anambra, and from Anaocha local government area. When people described my complexion in Nigeria, they called me light-skinned and fair in complexion, and sometimes, they just called me yellow. ‘That yellow Igbo girl’ was a regular description, and I never fought it. I still do not fight it.

Then I moved to America where I became just black. It did not matter that I was from Anambra State. It did not matter that I was Igbo. It did not matter that I was Nigerian. It did not even matter much that I was African. It was only when I spoke and people heard my accent that there was a sudden interest in my origin. But generally, as far as America was concerned, I was just black. It was with reluctance – and sometimes even resentment – that I would tick the ‘Black’ or ‘African-American’ box on forms. I wanted to be recognized as Igbo, or at least, as Nigerian. I wanted America to know that my black was different from their black because I had been conditioned to believe that my black was not just different, but better.

And America did a premium mind fuckery on me. On one hand, I was complimented by white people for being a different kind of black. I was told that I was not at all like their black people, the American ones. No, I was proper, spoke articulately, and was always well-mannered. I basked in those compliments. In Nigerian lingo, my shoulders were rising, and I was prouding. But America was like the uncommitted boyfriend, sending me mixed messages, being here today and gone tomorrow, on today and off tomorrow, lukewarm and impossible to place or understand. America told me that I was the better black, but America also reminded me that while I was the better black, I was still just black. Did America like me or not? Did America want me or not? It felt like a boyfriend professing eternal, undying love and then ghosting me the next day. I was profoundly confused.

As a teenager, my tender and inexperienced mind just did not comprehend racism or the impact of slavery. Sure, I learned about them in the two years of high school I completed in America, but I still did not really understand them. To me, they were unlucky incidents that happened a long time ago but they were no longer happening or relevant. Why did black people keep bringing up these old things that were no longer issues? It was unfortunate, I concluded, that white people once enslaved black people, but black people were now liberated, so what were they complaining about? I, for example, could come from Nigeria into America and start a new life, and I would succeed and even surpass the black people that were here before me, so obviously, the system worked, and it was these black people who were refusing to work hard. They needed to be more like us, the better black people.

I think I thought my bracelet was a watch.

As a Nigerian, it was normal to see my fellow Nigerians come into America and work three to four jobs while going to school fulltime and taking care of their family in America and in Nigeria. Again, why were black people complaining? Maybe if they would stop selling drugs, giving birth to bastard babies, and committing crimes, all would be well with them. America was a land filled with opportunities. If I, an outsider, could make it in America, then the citizens of America, regardless of their color, had no excuse.

Then I got older. And I made a conscious effort to understand. And I made a conscious effort to put myself in the shoes of these black people that I thought I was better than. And I began to understand that being enslaved with chains and shackles around your feet was the slightest slavery, and that the real slavery was in the mind. The most hard-hitting discovery, however, was realizing – or remembering, maybe – that these black people were African people who were now in America because their fellow African friends and relatives sold them for shiny piece of mirror. It was me realizing that I was them and they were me, and the only difference was that I came here by choice. It was an inconvenient discovery that birthed an anger in me because things were different now. I could not unknow what I knew.

Nigeria did not teach me about slavery. Nigeria did not even teach me about its own civil war, so how could I expect to learn about America’s war on racism and slavery? I learned that not having an ancestor who was a slave did not mean that such ancestors did not exist; it just meant that I knew nothing of them because Nigeria failed to tell me about them. America, conversely, convinced me that I was not one of them, that I was different because I knew where I came from.

I remember when Obama became president of the United States. I was so happy to have a black man and his wife in the White House because I knew that it had never happened before. However, when he was declared as the winner, the emotions I felt were different from the emotions I witnessed from other black people. While I was happy, elated, and relieved, other black people were crying and in awe that they had lived to see this day. I, as a Nigerian, however, had known only black presidents. Nigeria is the most populous black nation on earth, so my reality was different. I only saw black presidents, and no one jumped up and down because our president was black. Of course, he was. What else was he going to be? It was a teachable moment for me.

I remember someone saying how proud she was of herself because she was the first doctor in her family. I was stunned because I was a child being raised by two medical doctors. My parents both had friends and relatives who were also medical doctors, and even in my own circle, one of my closest friends was in school to be a medical doctor. I was used to having people who were medical doctors, lawyers, architects, and everything in between. I was used to seeing black people who were on television and thriving, and I was never told that any of my ancestors were enslaved or raped or lynched. It was not my reality. It was not my perspective.

The unfortunate irony for a lot of us, Africans, is that when we make it to America, the promised land flowing with milk and honey, we experience all kinds of culture shock, but the most shocking among them is when black people call us vile names, ask us how we got into America, if we lived on trees, and if we rode on elephants. White people, on the other hand, are usually softer on us. Sometimes it comes with ulterior motives, but at that time, in our vulnerability, we welcome them. It is like when a starving person meets a person who offers them mold-infested bread. It might ultimately make them sick, but first, it will put something in their belly.

I had no preconceived notions about black people when I came to America. My only preconceived notion was that things were easy in America, that I would excel and be very rich. But it was black people, through their words and actions toward me, that made me feel small and unwelcome. Those actions, by themselves and cumulatively, did not speak for the black community. I did not know it then, but I know it now.

In conversations with my African-American brothers and sisters, I am told that they are sometimes hostile toward Africans because Africans look down on them and think they are better than them. Africans, understandably, feel the same way, so we are left with the case of the chicken or the egg: which one came first? My people say that when two elephants fight, it is the ground that suffers. While Africans and African-Americans fight and argue over who started what and when, it is our children and our families that suffer, and this war, at the end of the day, is just a war between the black people that were enslaved and the black people that were colonized — by the white people.

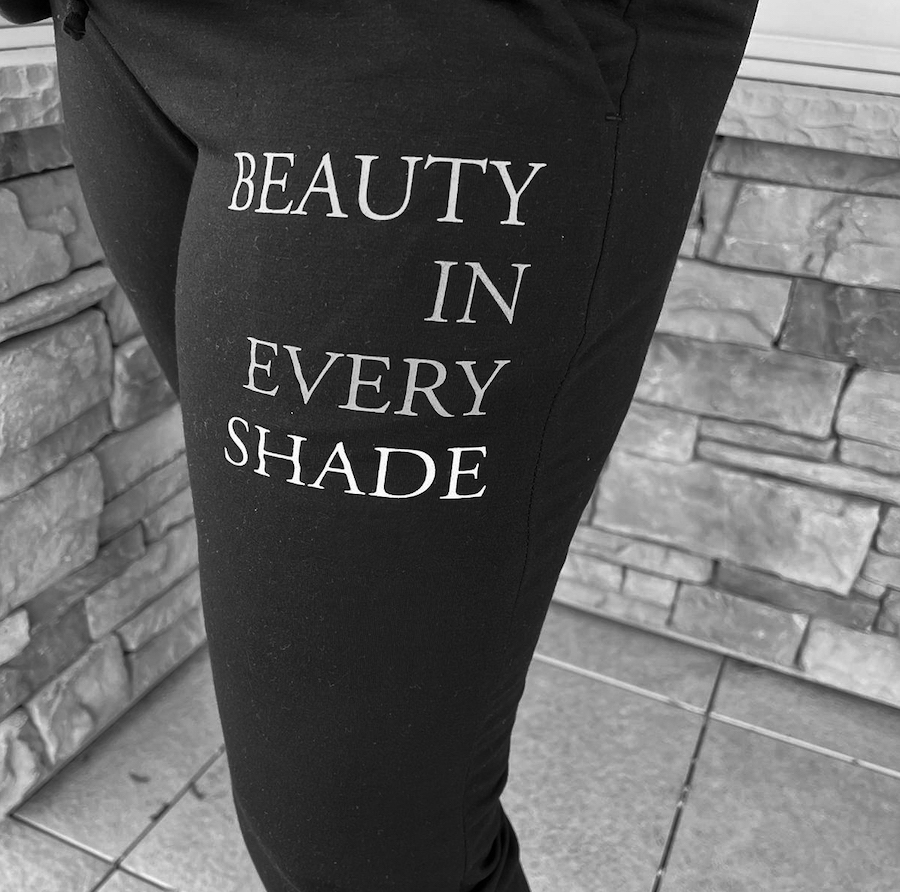

Today, as Black History Month officially commences, I am like a proud peacock, showing off all the colors and shades that make me beautiful. I do not take for granted the Igboness, the Nigerianess, the Africaness, and the blackness that have uniquely come together to forge me. I am proud that I get to be Igbo, Nigerian, American, and black.

I cannot help but be grateful for my ancestors who walked this path before me and made today possible for me. I wonder what went through their minds when they were forcefully separated from all that they knew and loved. And I wonder how far their dreams went when they were being flogged and starved on this land that was foreign to them, this land where their blood was spilled. Did they dream that one day, their descendants would come to America on their own, not bound or shackled? Did they know that one day, their descendants would give just about anything to live on this land that enslaved them – body, soul, spirit, and mind? Did they imagine that one day, an entire month would be dedicated to celebrating their blackness and story – and the month would be called Black History Month?

I closed my eyes while writing this, and I tried to picture it, what life was like for them. I tried to feel what they felt – the fear, the anger, the pain, the anguish, the hopelessness. The thought made my body shiver and my knees buckle. I cannot picture what they saw, and I cannot feel what they felt. All I can feel is a dimension and sphere of bleakness, the kind that kills.

Today, I say thank you. To my Chi (my living fate), to my akalaka (my destiny), to this very moment, and to God who was and who is. I am also eternally grateful to my ancestors, the sacrifices they made, and the price they paid. Because of them, I can and I am.

Happy Black History Month – this month and beyond.

This is profound Vera, and food for much thought. Happy Black History month. Proudly black, African and Nigerian

Thank you very much! Happy Black History Month to you too.

What a great read. I am still learning and letting go of my biases.

Thank you so much for reading, Neuyogi! Letting go and self improvement in general is a continuous journey because there is always room for growth. What matters is that you’re growing and moving forward.